Sometimes there can be nothing more satisfying than catching fish using a piece of equipment you’ve made yourself. If you’re a float fisherman, like many of us are, making your own floats is a natural progression. I was fortunate to have a great teacher, Mark “The Beast” Jeenes in Birmingham. A gentle giant of a man who enjoyed his life to the full and sometimes took on a very affable Viking persona.

We both worked in Greenway’s fishing tackle shop in Kingstanding and I learned so much in the company of Mark. He was a wonderful bloke, he happily imparted all the information he knew, including how to make and repair fishing rods and of course – how to make your own floats. He’s very sadly missed by all who knew him.

I made a load up in the shop thirty years ago, over the years I’ve given many away to admiring friends and I’d also lost or broken a few as well. Fishing peacock wagglers a lot, as I do on the Trent, my collection was getting depleted, so I recently made some new ones.

Making Peacock Wagglers

By far the best material to use is peacock quill. It is very light and buoyant; it casts well too! The main problem with peacock quill is that it is not the straightest material to use – although there are ways to combat this.

The first issue I had was to locate peacock quill, I’d been led to believe that it was difficult to acquire these days. A quick search on the internet found this to be untrue though, I secured some quite easily, inevitably from China. My friends Andy Gammon and Terry Trueman also had some spare too, which was useful to get started.

To make floats you need some basic materials and some tools which are:

Materials –

- Peacock quill.

- Cane BBQ skewers.

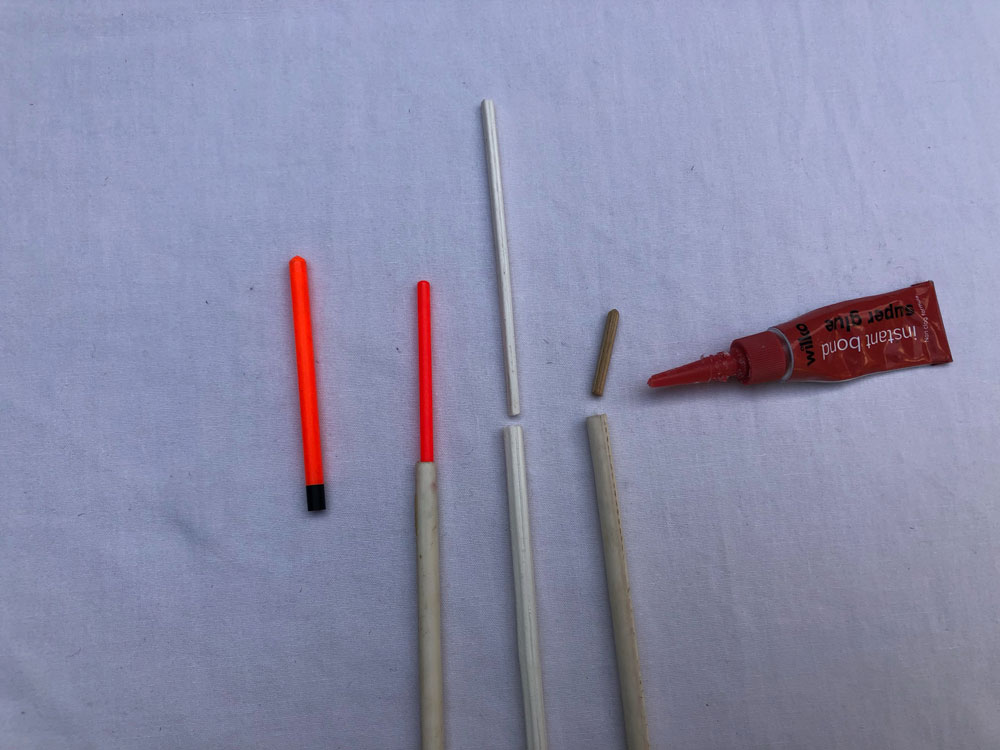

- Hollow fluorescent tip inserts.

- Super glue.

- White enamel paint.

- Fluorescent orange or yellow paint.

- Matt black/grey wood-metal paint.

- Gloss varnish.

Tools –

- Fine and ultra-fine glass paper.

- Fine metal hack saw.

- Scissors.

- 2mm metal drill bit.

- Scalpel or Stanley knife blade.

- Quality fine art paint brush.

- White spirit.

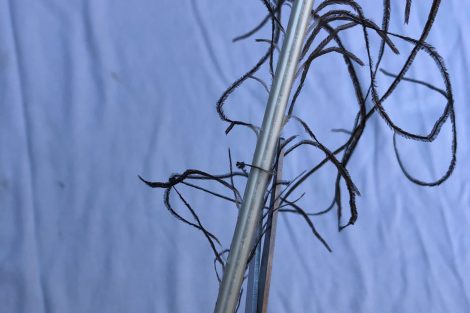

Some peacock quill comes cut in 50 to 60cm lengths, while others will have the full plume. You will need to cut the herl (stringy bits) away from the main quill with a pair of scissors, trying not to pull them off as it can peel all the way down and you lose what you need to make a float. Then sand them down until any rough bits of herl have disappeared.

The herl you’ve cut away doesn’t need to be chucked. If you tie fishing flies or know somebody who does, it’s a prerequisite for some of the most famous fly patterns.

Selecting the peacock quill for the type of float you want to make is important. Firstly, for the longest floats, you want to select the straightest pieces possible. If you want to make thicker straight peacock wagglers, without inserts, you need to select the thicker stems.

I tend to grade my quill into three or four groups, depending on what I want to make. The golden rule is that the longer the float, the straighter the quill needs to be, this will save you a lot of hassle later, trust me!

Once you’ve done this, you’re ready to cut your quill to the size of the floats you’re making. To make a range in different sizes, I tend to cut a small piece off first, put a temporary cane bottom in it and float it in a water filled tube to check the buoyancy of the quill. I like to find a piece that takes 2AAA first and then work from there. If you’re lucky you might get three or four floats from a straight piece of full-length quill. If you’re making extra-long floats, you might only get one.

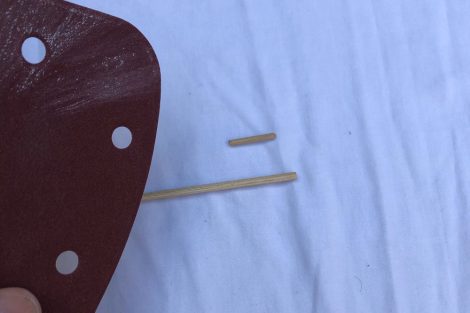

Once you’ve cut your quill, it’s time to make the cane inserts for the bottom where the peacock waggler adapters will fit. I cut mine about 40mm long. This means you’ll have a decent length of cane glued inside the quill which adds strength and enough to attach the waggler adapter. Cut with a hack saw and then round one end off with glass paper.

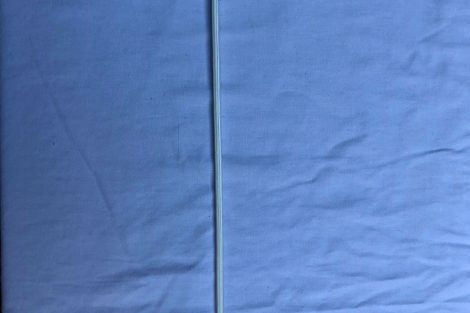

Using your fingers, carefully drill a hole at the bottom end of the quill using the drill bit to about 15 to 20mm deep. Keep the drill as straight as you can, over time this process gets easier the more you do it. If you’re putting inserts in, it’s the same process at the other end. Take your time, as you want everything to be as straight as possible. I dry fit everything before I start glueing to make sure everything is straight. When you start to glue, make sure you take your time so that everything is as straight as it can be.

I’ve moved over to pre-prepared fluorescent hollow inserts now. They’re better in changeable light conditions, but you can make inserts from thinner bits of quill if you wish.

If you’ve got some slightly bent quill, all is not lost. It can be straightened by bending or creasing it in the opposite direction of the bend. It might take three to four creases up the length of the quill to straighten it. This process will weaken the quill, so you will need to strengthen it again. Putting small drops of superglue around the creases does this. Spread it in and on either side of the creases and leave it to dry for a few hours. I’ve also heard of a steaming technique that will straighten a quill out, I’ve never done this as I found the crease and glue method works fine.

Once thoroughly dry, it is time to use the ultrafine glass paper to smooth any excess glue and any rough edges. Pay special attention to any glued areas or areas with any ridges so you can get a smooth finish that will enable your finished float to have a shop like finish.

With the construction phase over, it’s time to paint them. If you’re painting your tips or tops fluorescent, they will require an undercoat of white first. You can then apply the fluorescent colour. You can either paint them with a brush, which could take two coats, or you could drip coat them (called dripping). Dripping requires patience and practice to get rid of the excess drips, but a more bulbous finish can be achieved.

Apply your main body colour afterwards, I use matt black, but the colour choice is up to you. I give them at least three coats and a very gentle sand with the finest ultrafine glass paper before I apply the last coat, this helps to get the smoothest finish possible.

After painting, once the floats are fully dry, the cane bottom will need varnishing. I use a water-based rod varnish, but any gloss varnish will do. Depending on the type and make of varnish, this may require a couple of coats.

And that is it. Following the above, you should have some great floats to fish with. There are a lot of things to experiment when making your own floats. Some of you may prefer some loaded floats or bodied wagglers, others loaded sliders or just some ultra-long peacock wagglers for deep venues or windy conditions.

I’ve been testing some peacock wagglers on the Trent recently which are up to two feet long in twelve feet of water. The idea is that because the float is longer, it enables you to fish a 14ft rod instead of a 15ft rod. The results have been promising so far, I’ve not felt I’ve missed bites because my line is deeper in the water, which might be an issue when using such a long float. Longer floats are also susceptible to bending in more extreme temperatures, particularly cold ones.

More time fishing is needed with them to prove that this is a viable tactic to employ. It does prove though that by making your own floats you can design them specifically to how you want to fish, which you could never do buying off the shelf from a tackle shop.

At the end of the process, you’ll find you’ll have lots of quill offcuts left over, these can also be used to make wonderful floats. Two, three or even four-piece stepped peacock wagglers can be made quite easily if you stick to the basic principles of taking your time and care over each float and keeping things as straight as possible. There will be very little waste if you put your mind to it.

So, there it is, something to do over the long winter nights and it might just catch you a few more fish. What could be better than catching on a float you’ve personally made.

Next, I’ll look at making some pole floats.

Until next time, Tight Lines!